George Gissing’s Workers in the Dawn (1880) is an extraordinarily ambitious first novel that is complex (though less than concise) in its construction, serious (though problematically misogynistic) in its engagement with social realities such as alcoholism and prostitution, brave in its inscription of a tragic suicidal end for its main character, and valuable in its documentary reference to under-recorded but significant historical phenomena such as the working-class reception of the 1871 Commune in Paris. In a narrative that in some respects resembles Henry James’s The Princess Casamassima (1886), Workers in the Dawn traces the story of an unusually handsome boy, noble of blood but born into poverty, who comes into contact but becomes disillusioned with late nineteenth-century London’s newly prominent left-wing politics. Like Hyacinth Robinson in James’s novel, Gissing’s Arthur Golding gains an incomplete education and works as a youth with artisans in the book trade (Hyacinth is a bookbinder; Arthur, a printer). Both characters display some sort of artistic propensity which is never allowed to play itself out, and both novels, therefore, instantiate stunted forms of the Künstlerroman, wherein the self-actualization of the male lead is only ever mooted and never achieved. (Golding: ”When shall I have my first picture in the Academy?’ (185) Fate: ‘Never.’)

Like The Princess Casamassima, Gissing’s novel deserves to be recognised as one of the great London novels of the period, and was, indeed, one of the key initiators of the flourishing in the latter two decades of the century of the grittier sort of urban fiction of which James’s book is a lauded example. Gissing became famous later on in the decade for writing fiction set in very poor, slummy parts of London, such as Clerkenwell (see The Nether World (1889)): the geography of Workers in the Dawn includes these kinds of settings (notably in its opening chapter, which plucks an orphan from Whitecross Street, reputedly ‘the worst street in London’), but is largely drawn from the more socially mixed localities of Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia. As Richard Dennis has traced (2009), the series of temporary addresses at which the unfortunate hero resides mirrors very closely the residential trajectory of lodging and boarding houses the novelist himself plotted. While the novel has long been recognised as partly autobiographical, being often described as containing a fictionalized rendering of the early years of his life which he spent with Nell Harrison (the ‘rescued’ prostitute and alcoholic he unhappily married) the recent spatial turn in scholarship has demonstrated the novel is at its truest-to-life in its choice of residential locations.

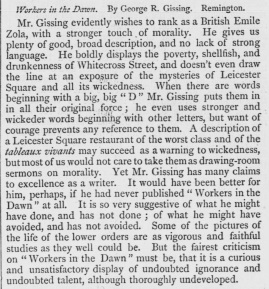

Though unaware of the novel’s autobiographical use of London, the reviewer in the Examiner (July 17, 1880) still recognised its geographical interest as one of Gissing’s chief literary innovations, picking up specifically on his inclusion of the ‘shellfish’ of the slums and, more codedly, the ‘mysteries’ (prostitution) of Leicester Square. I include the piece here complete:

In addition to marking the novel’s ‘bold’ representation of the metropolis, however, the review also treats questions of literary geography in other respects too. Both in the way its first sentence notes Gissing’s evident elective affinities with the French naturalist tradition, and in its italicized recourse to the French language (‘tableaux vivants‘) when gesturing to unspeakable continental vices, the reviewer in the Examiner seems to suggest that Zola’s Paris is somehow spectrally present throughout Workers in the Dawn, even though readers do not encounter it directly. (Paris is perhaps most forcibly legible in the text in the grotesque scene in which the working-class radical-cum-madman John Pether burns to death amidst the (both literally and metaphorically) incendiary newspaper reports of the Commune he has been poring over in bed.) It is interesting that while the review points out that Parisian naturalism is in the background of this London novel, it also implicitly insists that Gissing might have done more to bring this fully scandalous French affiliation into the light. Hinting that the doubtless ‘talent[ed]’ author suffered from an English failure of nerve, perhaps deriving from too conflicted a desire simultaneously to ape Zola’s uncompromising naturalism and to inject a ‘stronger touch of morality’ into the mix, the review claims that Gissing’s novel suggests not only what it ‘might have avoided’ but also what it ‘has not done.’ Though hidden beneath an apparently harsh judgement that the novel would have better gone unpublished, the Examiner‘s fair critique of Gissing’s contradictory mash-up of French descriptivism and English prescriptivism recognises the intellectual potential of Workers as much as it chides its failure in execution.

One key aspect of the novel’s spectrally Parisian London geography is its repeated focus on multiple occupancy housing. As Sharon Marcus (1999) has shown, despite the fact that lodging- and boarding-houses were extremely common in nineteenth-century London, the English capital preferred to imagine itself as a city characterised by neatly defined town-houses inhabited by only one family each, in contradistinction to the promiscuous disorder of apartment-living the Parisians put up with. In the nineteenth-century English cultural imagination, there was something other, something French, about sharing a front-door with co-nomadic strangers. But Gissing’s novel eschews this pretence at lodging’s otherness by showing the practice as ubiquitous, depicting one boarding- or lodging-house after another, of varying qualities and housing characters across a range of class positions, from the nightmarish site in Whitecross Street at the very beginning to the first-floor lodgings let out to Augustus Whiffle, a lazy middle-class student of divinity (221). Those fairly well-appointed rooms of Whiffle’s, like several let out to Golding, are located in Bloomsbury, the part of London this novel constructs most thoroughly. Gissing presents Bloomsbury as he had found it: an area characterised by an unusual degree of class mixture, with a plethora of multiple occupancy housing that catered to a very wide spectrum of society. In doing so, the novel offers a series of variations upon the Bloomsbury boarding house, a literary space Gissing knew not only from direct experience, having inherited it from Dickens and Trollope. In Workers in the Dawn, this site that had been treated in farcical or tragicomic terms by those earlier writers becomes modulated with a naturalism that pays overt homage to Zola, thereby acknowledging a covert French-ness that, according to Sharon Marcus, had been there all along.

George Gissing, Workers in the Dawn ed. Debbie Harrison (Victorian Secrets, 2010).